What makes a great portrait?

Jan 8, 2025

I certainly do not claim to be the ultimate judge of what makes a good portrait, nor would I suggest that my attempts perfectly capture the “truth” of my subjects. However, over the years, I have developed somewhat an eye for images that stand out—those rare photographs that linger in the mind. In this pursuit, I found inspiration in the wisdom of Nadar, the 19th-century pioneer of photography, who famously said:

“The theory of photography can be taught in an hour. The art of photography cannot be learned in a lifetime… What is a portrait? A likeness? But what is likeness? The thing is to take a portrait as only one in a thousand can take it.”

For Nadar, a portrait was never just a record of someone’s features. A real portrait, he suggested, requires connection, intuition, and the ability to see beyond the visible. This concerns revealing something essential, something the subject might not even be aware of themselves. And therein lies the fundamental challenge of portraiture—not merely to see your subject, but to understand them.

The Limits of Technology

Modern cameras make it easy to create sharp, well-exposed, and technically balanced images with minimal input. But a camera, no matter how advanced, cannot replace the human element. It does not understand whether you want an image to feel dark and introspective or bright and joyous. It simply calculates what it considers “correct” settings—often a good starting point but rarely enough for a truly great portrait.

To transcend the mechanical, we must approach photography with intent. This begins by manually adjusting the key settings to align with the mood we wish to convey. From there, the next critical consideration is light: Is it soft, hard, bright, gentle? Each type of light has its place. Contrary to popular belief, not every portrait demands soft, flattering light. Harsh or directional light can create striking effects when used with purpose.

Framing the Feeling

Once you’ve chosen your camera settings and lighting, the next decision is framing. This is where the image begins to take shape, and the choices you make will profoundly affect its emotional impact. What is in the background? How much of the frame is in focus? How wide is your shot? How far are you from the subject?

Each of these decisions influences the feeling your portrait conveys. A classic 85mm lens might produce a polished, flattering image. A wider lens, such as a 50mm or even a 35mm (one of my favourites), can create a more intimate perspective that draws the viewer closer to the subject’s world. There are no universal rules here—just possibilities. The purpose is to make choices that serve the story you want your image to tell.

The Role of Equipment

While equipment matters, it is always secondary to vision and intent. Most modern cameras are more than capable of producing excellent portraits. That said, factors such as sensor size, lens character, aperture, and filters do indeed play a role in shaping the final image and should, whenever possible, be chosen deliberately to suit the mood and style you are aiming for.

But never let equipment limit your creativity. As the adage goes, the best camera is the one you have with you. Great portraits come not from the gear, but from the connection between the photographer and the subject.

The Human Element

Ultimately, the most important aspect of portraiture is not the camera, the lens, or even the light—it is the connection between you and your subject. As Nadar understood, a great portrait is a collaboration—an ability to create a space where your subject can be seen as they truly are.

How do you make someone feel at ease? How do you evoke an emotion or reveal something deeper? These are intangible skills, honed over time. They are the “je ne sais quoi” of portait photography, the spark that transforms a good image into a remarkable one.

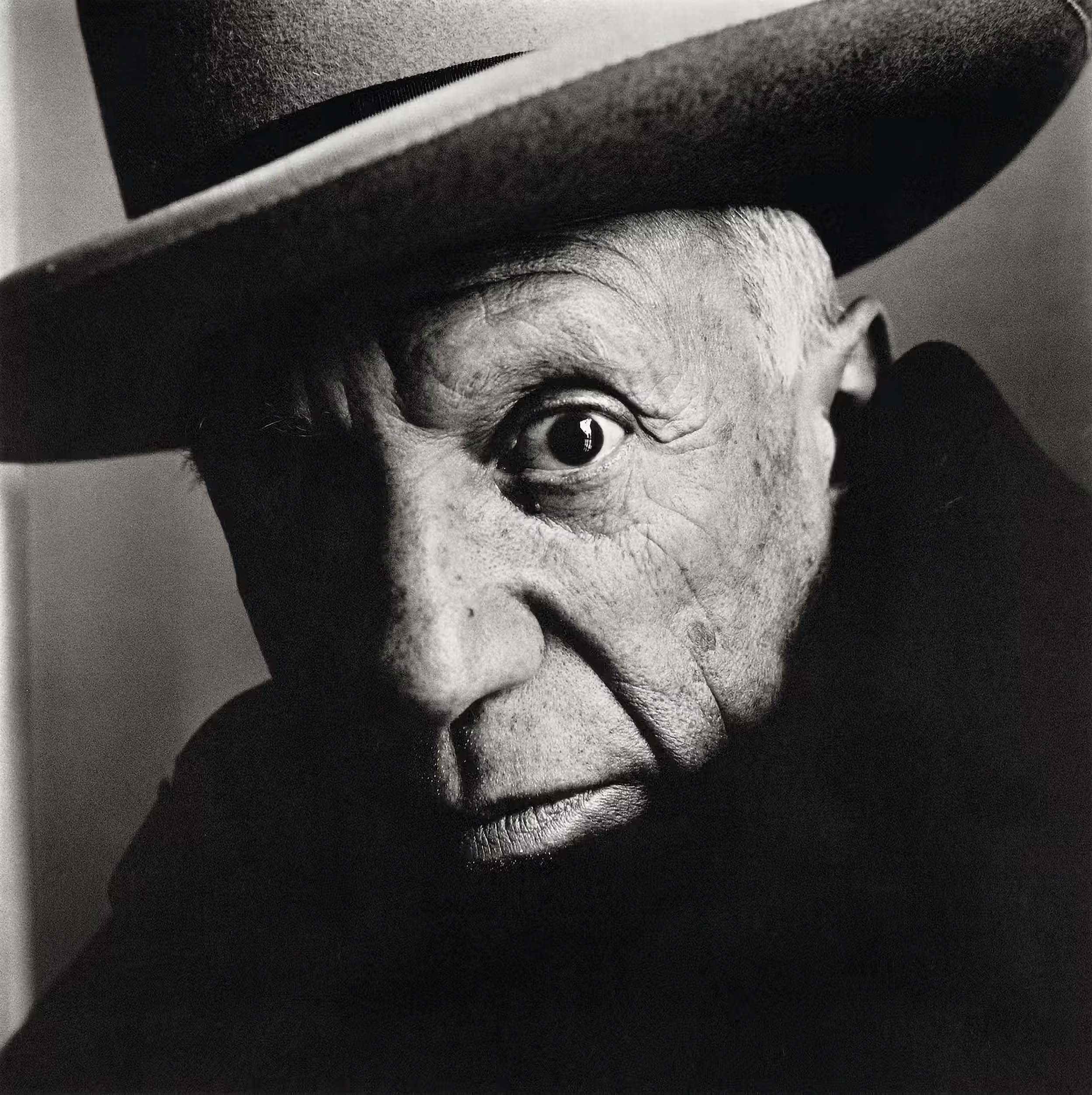

Sometimes, the connection between subject and photographer is shaped as much by circumstance as by creativity. Take Irving Penn’s famous 1957 portrait of Pablo Picasso. Penn was determined to photograph the artist but faced a wall of resistance from Picasso’s entourage. Undeterred, Penn took matters into his own hands, quite literally forcing his way into a meeting with the painter. When the opportunity finally came, he captured a hauntingly intimate image of Picasso.

Pablo Picasso at Cannes, by Irvin Penn

Framed by the shadow of his hat, with a single intense eye staring directly at the camera, the portrait is as much about Picasso’s commanding presence as it is about Penn’s persistence. This image has since become one of the defining portraits of Picasso, and one could argue the unorthodox approach revealed an element of Picasso which would have been hidden with more easy-going approaches.

In contrast, other photographers might strive to evoke wonder, joy, or introspection. Each approach is valid, provided it aligns with the story you wish to tell. The best portraits do not necessarily impose a mood but discover one. Talk to your subject. Observe them. Understand who they are and allow them to feel comfortable enough to be themselves. When this happens, you might capture something extraordinary: a glimpse of their essence, something even they did not know about themselves.

And that, perhaps, is the heart of great portraiture—not just to see, but to reveal.

STAY in the loop

Receive updates on new posts—no spam, only thoughtful content.